The opening of a war museum in a small town of northern France recently has been welcomed by Ashburton woman Jackie Rapley whose late father fought there.

The New Zealand Liberation Museum – Te Arawhata in Le Quesnoy commemorates the courage of New Zealand soldiers who famously liberated the town from German occupation in World War One.

Jackie took her own pilgrimage to Le Quesnoy five years ago, remembering the service of her late father Jack Hughes of Ashburton.

She was attending the 100th commemoration of the liberation, when the museum was still in its early planning stages.

While Jackie did not travel over there again this time to see the opening, she had watched from afar and been thrilled to see it come to fruition.

‘‘I am delighted that the New Zealand Liberation Museum is now open in a beautiful old building in the town of Le Quesnoy,’’ Jackie said.

‘‘My hope is that it will be a place for Kiwis, especially young ones, to discover, remember and honour what their forebears did in both world wars. I know it is going to be a very special place,’’ she said.

The museum has been established by a New Zealand trust, which used donations and fundraising to refit a former mayor’s residence.

Hughes was a war-wounded soldier when he served with the 3rd Battalion, New Zealand Rifle Brigade, at the time of the battalion’s involvement in the liberation in 1918.

Wētā Workshop set up some of the exhibits, and inset: Jack Hughes of 3rd Battalion NZ Rifle Brigade.

The New Zealand Liberation Museum in Le Quesnoy, opened last month, takes its name from the resourceful way New Zealand soldiers used a ladder to scale the town walls.

It was November 4, 1918, and they liberated the demoralised and hungry people of Le Quesnoy who had suffered four years of German occupation. A symbolic piece in the museum is the large scale 7.4m high ladder.

As well as being a central part of the story of liberation, it represents a pathway to gaining a higher level of knowledge. The original 9m ladder was acquired from a local orchard.

Jackie said it had been a serendipitous finding when she learned her father’s war service was part of the Le Quesnoy story.

She said while growing up, her father had not talked much about the war.

She knew he fought on the Western Front in the Somme and was shot and wounded in the Battle of Messines in 1917, but had been unaware of his involvement in the liberation of Le Quesnoy.

‘‘Chance is a funny thing. I have treasured maps he brought home with him, but because they are 100 years old, and fragile, and because they are of unfamiliar territory, I had not looked at them much,’’ she said.

‘‘This changed when I was able to have them copied and felt more comfortable looking at them.

“I started Googling the little towns named on the maps and on Googling Le Quesnoy, up came lots of information about this small northern French town, and lots and lots of information about the New Zealand Army’s liberation of the town.

“I discovered the 3rd rifle brigade had been involved and I was hooked.’’

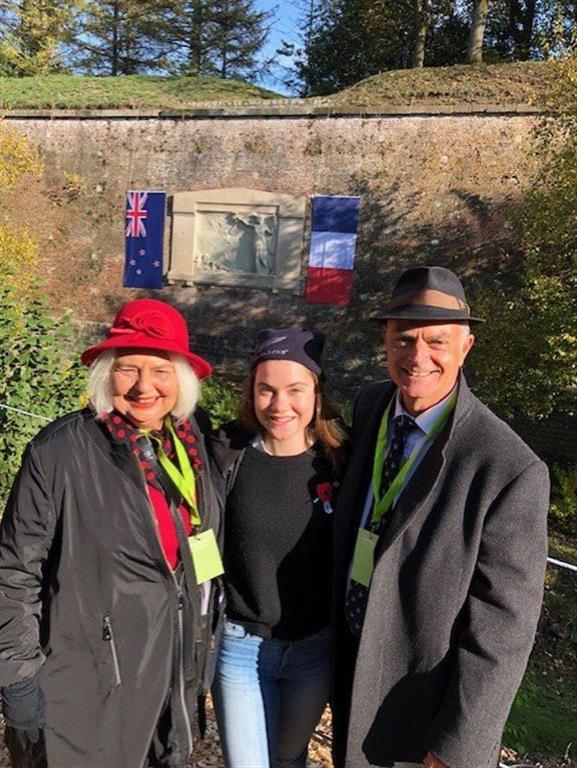

Her following trip to Le Quesnoy in 2018 had been at the prompting of her son James. The pair travelled to France, where James’ daughter Lucia was as an AFS exchange student.

The trio attended the 100th anniversary commemorations of the liberation.

‘‘To stand on the cobble-stoned square where dad had stood when the town was liberated was very special,’’ Jackie said.

Hughes was a farmer working at Waitohi Flat when at the age of 21 he enlisted in the New Zealand Army and served in World War One from April 3, 1916, to June 7, 1919. Upon his return he settled in Ashburton.

Jackie was 29 when he died in 1973.

‘‘He was a good, kind, caring father,’’ she said. ‘‘He was a lovely man. He was very stoic, never complained, and was incredibly hard working.’’

‘‘My dad was both a gentleman and a gentle man.

‘‘I remember being about 15 and going to a war movie and he growled at me, and he never growled. He said ‘ Jack’, as he called me, ‘War isn’t entertainment’.

‘‘He had strong feelings about war and how it wasn’t good due to the horrors he had experienced and seen.’’

His war wound affected his whole life. From being shot in the arm he lost muscle and had two ‘‘destroyed’’ fingers, which were ‘‘crooked into his left hand’’.

The New Zealand assault in 1918 began at 5.30am with an intense barrage and a smoke screen created by burning oil-filled drums. By 9am they had the town surrounded.

A day-long battle ensued outside the walls with fierce German opposition.

When the Germans refused to surrender, the riflemen decided to try a direct assault.

After several failed attempts they succeeded in placing the ladder at 4pm. This was climbed and shots fired. With riflemen now starting to flood into the town, and street battles continuing, the German garrison surrendered.

The division had taken 2000 German prisoners and 60 field guns. Before the day was out, 118 Kiwi soldiers would die, with another 24 dying of their injuries within the next month. A further 300 were injured.

The people of Le Quesnoy never forgot the sacrifice of the young men who came from the other side of the world to save them.

Every year they mark Anzac Day, while New Zealand geography and culture is part of the curriculum of primary schools.

Street names are inspired by New Zealand, including Place des All Blacks and Rue du Docteur Averill. The latter was named after Second Lieutenant Leslie Averill who was the first to ascend the ladder, and after the war became a well-known Christchurch doctor.

In the new museum, Peter Jackson and Wētā Workshop created the exhibits. They include a giant figure of a Rifle Brigade soldier holding winter flowers from Northern France.

Of the 142 New Zealanders who died in the liberation of Le Quesnoy, 80 were from Hughes’ division.

The museum was opened by former New Zealand Governor General Sir Jerry Mateparae and the Mayor of Le Quesnoy Marie-Sophie Lesne on October 11.