Soldiers surviving the gruelling battlefields of World War 1 were often too traumatised to tell their families about it.

Robert Allan Bruce (Allan Bruce) of Staveley fought in the war and was wounded at Gallipoli, but he would sometimes share his experiences.

Leading up to Anzac Day, Susan Sandys spoke to his son Richie Bruce.

At the age of 19, Allan Bruce enlisted with the New Zealand Army.

In the South Canterbury Mounted Rifles, he was among troops who set sale from Lyttelton with their horses for Egypt in 1914, to fight in World War 1.

Allan became a corporal and served through to the end of the war in 1918.

He survived and returned home, where he was able to marry Fan Dixon and have five children. He passed away in 1975 at the age of 80.

Today his son Richie Bruce, 84, of Staveley is a reposit of war memories of his father.

‘‘He didn’t dwell on them, but he was very ready to share them if you asked him,’’ Richie said.

‘‘Anything that I asked him,’’ he said. ‘‘And some of it was bloody rugged.’’

Probably the most rugged story of all was when Allan was wounded at Gallipoli, surviving as others died alongside him.

Late in the afternoon of August 21 in 1915, during a misguided attempt to try to take Hill 60, Allan and other soldiers had a grim task ahead.

It was to run up a gully towards the enemy, jumping out at the top.

The enemy Allan Bruce and his fellow Kiwi soldiers were facing, was Turkish machine gunners.

They were mowing down dozens of soldiers in a front moving towards them, including the soldiers leaving the gully.

Allan was shot, and managed to get to a scrubby bush where he and seven other soldiers sheltered from the barrage of fire.

From here, they could successfully use their guns to snipe at the machine gunner who had shot them.

They succeeded in this mission, taking out the Turkish soldier.

Their fellow Kiwi troops were then able to gain possession of the weapon.

Rescue for the group under the bush, from regimental stretcher bearers, did not come until the next day.

That was too late for all of them, but one.

‘‘In the morning, my father was the only one alive.’’

Allan had been shot in the middle of his upper leg; the bullet having travelled through and then into and out of his calf muscle. He had four open wounds; an entry and exit point on both his upper and lower leg.

A British army surgeon classified the injured to go by hospital ship to either Alexandria in Egypt, or England.

‘‘They were being drafted on the beach,’’ Richie said.

The army surgeon said to Allan he would go to Alexandria, and ‘‘We will have your leg off’’.

‘‘My father said ‘No, I want to go to England and leave my leg alone’.’’

Allan had understood anyone with serious wounds who went to Alexandria died.

The surgeon told Allan ‘‘You will do as you are told’’, to which Allan showed a revolver and said ‘‘Well, I have got this, I will say what happens to me’’.

The surgeon was swayed. He said ‘‘Off you go to England’’.

But as the Kiwi soldier was carried away, the surgeon wanted to have the last say and shouted after Allan and others around ‘‘You will probably die anyway and get that gun off him’’.

Upon the hospital ship, Allan wondered why it smelt so bad on the days-long voyage, but realised later the odour was from his own leg.

When dressings applied in Gallipoli were removed in England, he saw maggots had cleaned the wounds.

That was the story of his father surviving Gallipoli.

‘‘I only heard him tell it twice. He didn’t make a thing of it. Once to me, and once to someone else who asked. He never boasted about it.’’

Allan also shared with his son a light-hearted story from Gallipoli, showing that not all memories from the war torn Turkish peninsula were bad.

This was about how he learned how to make chapati, an Indian flatbread.

Allan had been sent on a message to Indian troops, when they showed him how they were using the base of a shell case to cook the chapati.

On the half-day walk back, as Allan hopped from gully to gully to avoid enemy fire, he managed to pick up wild tomatoes and quail eggs.

Upon his return he was able to make up a concoction using the gathered ingredients and army ration staples of biscuits and bully beef (canned corn beef).

He ground up the biscuits to make the chapati, cooking it in a shell case just as he had learned.

‘‘That was the best meal he had on Gallipoli.’’

Allan recovered from his wounds and went on to serve at the Somme and Passchendale.

His war service also featured a connection with one of the bestknown aces of the war, Red Baron German fighter pilot Manfred von Richthofen.

Allan was among soldiers in 1918 who guarded where the Red Baron finally met his end in France, as the crash site was targeted by souvenir hunters.

Richie was 37 when his father died.

He said he was full of love and admiration for the man who was ‘‘very quick to assess things’’ and ‘‘very quick to lend a hand’’.

‘‘He didn’t suffer fools lightly, he was very quick to make up his mind, he was always helping people.’’

While the bullet wounds received at Gallipoli had left lifelong scars on his leg, Allan did not have a limp.

‘‘In his 60s he was very agile, it was only when his eyesight went that it slowed him down.’’

And Allan’s practical nature had helped when it came to dealing with the trauma of war.

‘‘I believed until recently he showed no signs of war trauma. But I now believe he kept himself busy. I believe he didn’t dwell on things.’’

Among his traumas was the ‘‘enormously regretful’’ loss of his brother Harry, who was killed on Gallipoli after being hit in the head by a shell. Another brother, Roy, also fought in the war, and survived.

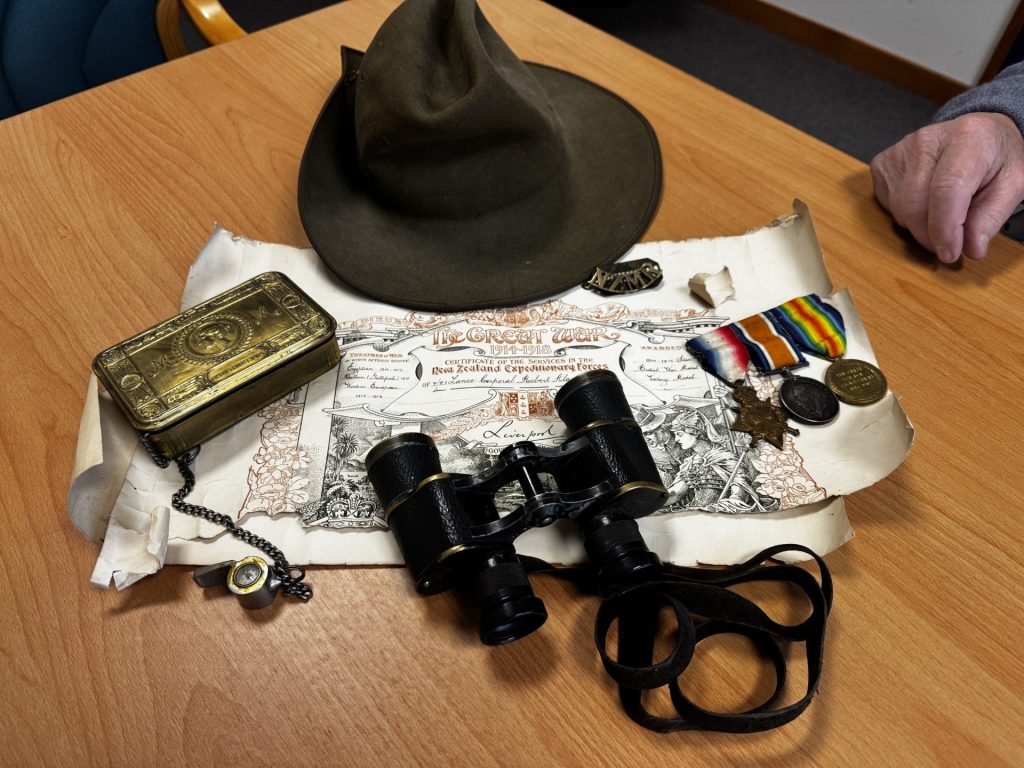

Richie has war items from his father today, including his service medals, slouch hat, tobacco box, trench whistle, and binoculars.